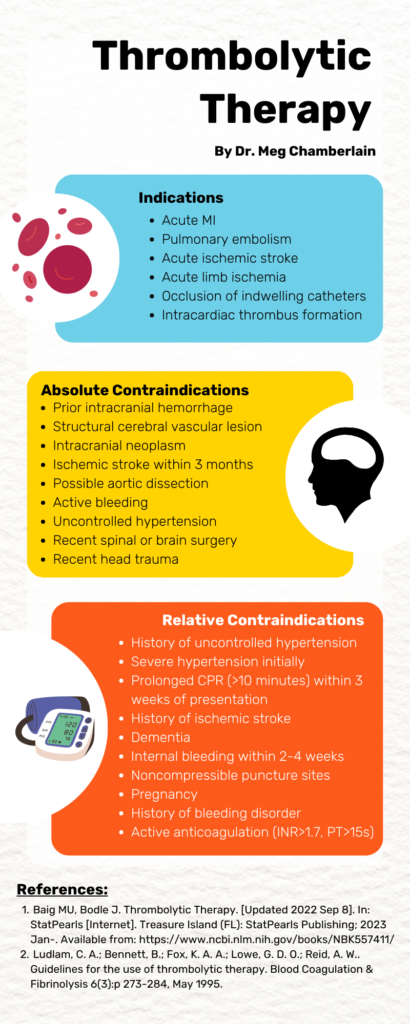

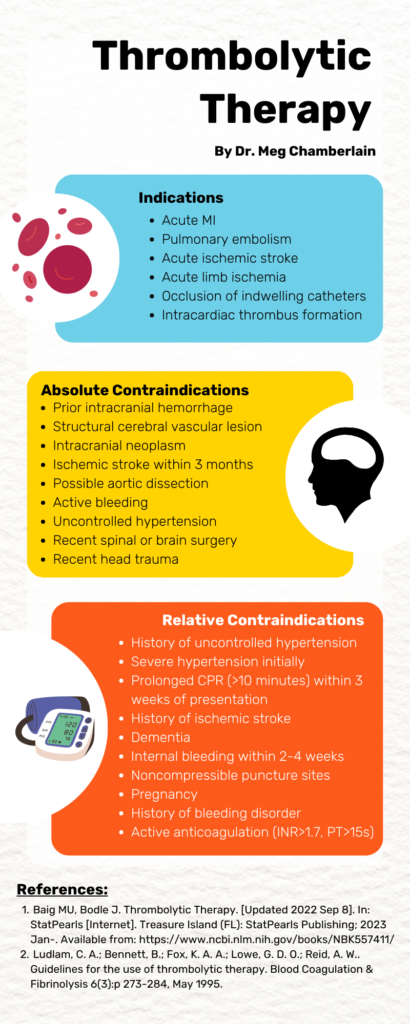

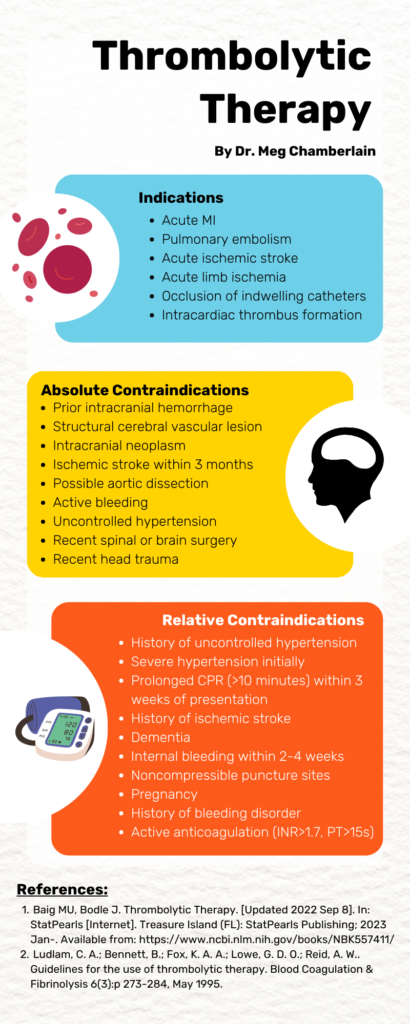

Thrombolytic Therapy by Dr. Meg Chamberlain

A 60 year old woman with a past medical history of HTN, HLD, and recent TIA now on Aspirin and Eliquis presents to the ED with one month of crampy, intermittent abdominal pain. She describes feeling sharp cramps in the epigastric region which typically last a couple of minutes and then resolve on their own. She cannot recall any exacerbating or relieving factors. She does not have any associated nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, or dysuria. She is currently without pain. On exam, her abdomen is non-tender without any rebound or guarding. POCUS findings are as below. What’s the diagnosis?

Answer: Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm with impending rupture

References:

Case: A 35 year old Hispanic male presents to the Emergency Department for acute onset weakness, particularly in the bilateral upper and lower extremities. Symptoms started abruptly last night after a stressful work day. He denies any recent illnesses, insect bites, or rashes. Vitals are within normal limits. On exam, there is pronounced weakness in his proximal muscles with his lower extremities slightly weaker than his upper extremities. His grip strength is preserved. Reflexes are normal.

Differential diagnosis includes: thyrotoxic periodic paralysis, hypokalemic periodic paralysis, myasthenic crisis, Guillain-Barre syndrome, transverse myelitis, tick paralysis

Case continued: Labs are notable for a potassium 1.7, magnesium 1.5, TSH < 0.01, Free T4 5.9, Free T3 23.5. EKG showing sinus rhythm with prolonged QTc. Management included IV and PO repletion of potassium which improved the patient’s symptoms rapidly. He was also started on methimazole for hyperthyroidism. Finally, he was admitted to a telemetry monitored bed to check serial BMPs and monitor for rebound hyperkalemia.

Teaching Pearls:

References:

Chaudhry MA, Wayangankar S. Thryotoxic Periodic Paralysis: A concise review of the literature. Curr Rheumatol Rev. 2016;12(3):190-194.

Kung AW. Clinical review: Thyrotoxic periodic paralysis: a diagnostic challenge. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006 Jul;91(7):2490-5. Epub 2006 Apr 11.

Vijayaumar A, Ashwath G, Thimmappa D. Thyrotoxic periodic paralysis: clinical challenges. J Thyroid Res 2014;2014:649502

A 30 year old female with a history of type 1 diabetes and past hospitalizations for diabetic ketoacidosis presents via EMS for altered mental status. History is limited as patient is altered and not answering questions appropriately. Vitals include Temp 100.4F, HR 116, BP 102/70, RR 30, SpO2 98% on room air. Exam shows an ill-appearing female with Kussmaul respirations and a non-focal neurologic exam. Labs are notable for 20K WBCs and serum glucose of 400. A lumbar puncture is performed to assess for meningitis. For this patient, which of the following CSF glucose values is within normal limits?

A: 60 mg/dL

B: 100 mg/dL

C: 260 mg/dL

D: 400 mg/dL

Answer: 260 mg/dL

This patient is presenting with signs and symptoms of diabetic ketoacidosis. While it is critical for the emergency physician to treat the hyperglycemia with volume resuscitation and insulin, it is also paramount to investigate for underlying causes such as infection. The glucose level in CSF is proportional to serum glucose values and should correspond to approximately 60-70% of serum glucose values. Thus, a CSF glucose value of 60 or 100 mg/dL in this patient is lower than expected and concerning for bacterial CNS infection. Higher than expected CSF glucose levels are non-specific and generally do not exceed 300 mg/dL.

References:

Lillian A. Mundt; Kristy Shanahan (2010). Graff’s Textbook of Routine Urinalysis and Body Fluids. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 237. ISBN 978-1582558752.

Seehusen DA, Reeves MM, Fomin DA (September 2003). “Cerebrospinal fluid analysis”. Am Fam Physician. 68 (6): 1103–8. PMID 14524396

A 19 year old female with a past medical history of autism and anxiety presents with right lower extremity swelling and pain. Two weeks ago, she developed right lower back pain with radiation into her right hip and leg which she describes as sore. She is sexually active and was started on hormonal contraception 2-3 months ago. Vital signs include BP 117/75, HR 108, RR 18, SpO2 99% RA, T 97.5F. The patient’s right lower extremity is neurovascularly intact with tenderness to palpation and swelling without color change. A right lower extremity ultrasound is shown below. What’s the diagnosis? How is this ultrasound performed?

Answer: Right Common Femoral and Popliteal DVT

DVT Ultrasound Evaluation: must evaluate at least 2 regions, typically femoral and popliteal veins

Femoral Vein

Popliteal Vein

DVT Ultrasound Pearls:

This patient received prompt anticoagulation in the ED and after being admitted, received a CT venogram revealing acute deep vein thrombosis in the infrahepatic inferior vena cava, bilateral common iliac, bilateral external iliac, bilateral internal iliac and bilateral common femoral veins requiring percutaneous mechanical thrombectomy!

References:

Baker M, Anjum F, dela Cruz J. Deep Venous Thrombosis Ultrasound Evaluation. [Updated 2023 Aug 8]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-.

A 74 year old male with a past medical history of advanced dementia and type 2 diabetes presents via EMS from his long term advanced care facility for cough and shortness of breath. Patient is AOx1 and intermittently follows commands at baseline. EMS reports that the facility nurse noticed that he was hypoxic and had a “nasty cough.” Vitals include Temp 100.6F, HR 110, BP 126/80, RR 22, SpO2 89% on room air. Exam shows a chronically ill, pale appearing older male in mild respiratory distress with a productive cough. Lung sounds are notable for crackles in the lower right lung. A chest x-ray demonstrates focal consolidations of the right middle and right lower lobes with a moderate sized pleural effusion above the right hemidiaphragm. Which of the following laboratory values is NOT part of the diagnostic criteria for an empyema?

A: pleural gram stain of culture

B: pleural LDH

C: pleural pH

D: pleural protein

Answer: pleural protein

This patient is presenting with pneumonia demonstrated by imaging results consistent with the clinical findings of fever, cough, and hypoxia. Pneumonia is the most common cause of an empyema which has specific diagnostic criteria distinct from the Light Criteria for pleural effusions. Approximately 40% of cases have negative cultures. Treatment is drainage and broad spectrum antibiotics with anaerobic coverage.

| Diagnostic Criteria for Empyema | Light Criteria for Exudative Pleural Effusion (requires 1 of the following) |

| Aspiration of grossly purulent fluid plus one of the following: | Pleural protein/serum protein > 0.5 |

| Positive gram stain or culture | Pleural LDH/serum LDH > 0.6 |

| Pleural fluid glucose < 40 | Pleural LDH > 2/3 upper limit of normal serum LDH |

| Pleural pH < 7.2 | |

| Pleural LDH > 1000 |

References:

Mace SE, Anderson E. Lung Empyema and Abscess. In: Tintinalli JE, Ma O, Yealy DM, Meckler GD, Stapczynski J, Cline DM, Thomas SH. eds. Tintinalli’s Emergency Medicine: A Comprehensive Study Guide, 9e. McGraw Hill; 2020.

Birkenkamp K, O’Horo JC, Kashyap R, et al: Empyema management: a cohort study evaluating antimicrobial therapy. J Infect 72: 537, 2016.

A 62 year old male with a history of coronary artery disease s/p recent cardiac stents, atrial fibrillation on Plavix and Eliquis presents to the ED with sudden onset headache, aphasia, and right sided facial deficits. A stroke alert is immediately activated, and non-contrast head CT imaging reveals the image below. What’s the diagnosis?

Answer: Subdural Hematoma

The patient’s anticoagulation was reversed with andexanet alfa. He additionally was provided with one unit of platelets and Keppra for seizure prophylaxis. Ultimately, the patient underwent embolization of the middle meningeal artery with significant clinical improvement of symptoms and was able to be discharged several days later.

Subdural Hematoma Pearls:

Eliquis reversal pearls:

References:

Cline, David, et al. “Head Trauma.” Tintinalli’s Emergency Medicine: A Comprehensive Study Guide, McGraw-Hill Education, New York, 2020.

Step 1: Modified Valsalva

Step 2: Escalating adenosine doses

Step 3: Attempt an infusion of a Calcium Channel Blocker

Step 4: If cardioverting, use propofol as sedative

References:

Lim SH, Anantharaman V, Teo WS, Chan YH. Slow infusion of calcium channel blockers compared with intravenous adenosine in the emergency treatment of supraventricular tachycardia. Resuscitation 2009; 80:523-528.

Bailey AM, Baum RA, Rose J, Humphries RL. High-Dose Adenosine for Treatment of Refractory Supraventricular Tachycardia in an Emergency Department of an Academic Medical Center: A Case Report and Literature Review. J Emerg Med. 2016 Mar;50(3):477-81.

Appelboam A, Mann C, et al. Postural modification to the standard Valsalva manoeuvre for emergency treatment of supraventricular tachycardias (REVERT): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2015; 386:1747-53

An 8 month old male born at 36 weeks without any complications with no medical problems who presents with wheezing, increased work of breathing, rhinorrhea and cough for the past 2 days. On exam, he has a low grade temperature, wheezing in all lung fields, subcostal retractions and nasal flaring. HR is 156 bpm, RR 70, Oxygen saturation is 90% on room air. Mother says other siblings in the house have had a cold the past few days. What is the next step in the management of this patient?

a. Administer IV dexamethasone

b. Administer broad spectrum IV antibiotics

c. Admit with supportive measures

d. Administer inhaled corticosteroids

Answer: Admit with supportive measures

This patient is presenting with acute signs and symptoms of bronchiolitis which include rhinorrhea, cough, wheezes, cough, crackles, use of accessory muscles, and nasal flaring. Babies born prematurely are at increased risk for severe bronchiolitis. Clinically, bronchiolitis occurs primarily <2 years of age, with a peak presentation between 6 and 12 months.

Treatment for bronchiolitis includes supportive care measures: nasal suctioning and saline drops, oxygen, isotonic fluids, and ventilatory support if needed. Consider hospitalization if persistent increased work of breathing, inability to maintain hydration/feeding, or hypoxia. Beta agonists can be trialed if the patient has a family history suggestive of asthma or atopy. Corticosteroids are not recommended for routine use.

References:

Bjoernsen, L. P., & Ebinger, A. (2016). Chapter 124 Wheezing in Infants and Children In Tintialli’s Emergency Medicine: A Comprehensive Study Guide (8th ed). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Education.

52 year old female with a history of breast cancer and recent unilateral mastectomy presents to the ED with the complaint of shortness of breath. Symptoms started earlier this evening and is accompanied by pleuritic, diffuse chest pain, dry cough as well as 4 days of left lateral calf pain. Vital signs include HR 112, RR 30, SpO2 89% on room air, BP 85/61, Temp 99.7F. Physical exam is notable for tachypnea, wheezing throughout all lung fields, and a tender, erythematous left calf. EKG demonstrates sinus tachycardia. A point-of-care cardiac ultrasound is shown below. What’s the most likely diagnosis, and what quantitative ultrasonographic measurement can be obtained to increase your post test probability?

Answer: Massive Pulmonary Embolism; Tricuspid Annular Plane Systolic Excursion (TAPSE)

Primary Use: TAPSE should be incorporated with McConnell sign, D Sign, RV Size and wall thickness and as well as with physical exam / HPI and your pretest probability to determine likelihood of PE. It cannot be used alone to diagnose PE due to the issues listed below.

Steps:

Limitations of TAPSE:

References:

https://www.emrap.org/corependium/search?q=TAPSE#h.sb6k765tgtm2

https://www.thepocusatlas.com/right-ventricular-dysfunction/