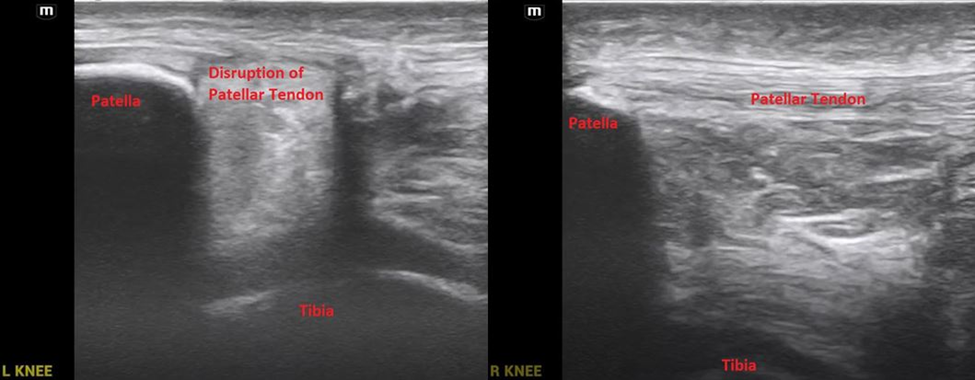

30 year old female is brought by EMS from an outpatient surgery center for evaluation of persistent hypotension and vaginal bleeding after an elective abortion and D&E at approximately 20 weeks gestation. Initial vitals on arrival were T 98.6 F, HR 99, BP 62/palp, RR 21, O2 100%. On exam, patient was pale and lethargic but mentation intact. There is scant vaginal bleeding on pelvic exam. A bedside FAST is performed and shown below. What is the interpretation of the FAST, and which views demonstrate free fluid if present?

Answer: Free Fluid in RUQ, LUQ, and Pelvis

The patient received 2 units of uncrossed pRBCs in addition to 1g TXA IV and was taken emergently to the OR with OBGYN for exploratory laparotomy. She was found to have 1500 ccs of hemoperitoneum from an actively bleeding R uterine artery laceration. She did well post-op and was discharged a few days later!

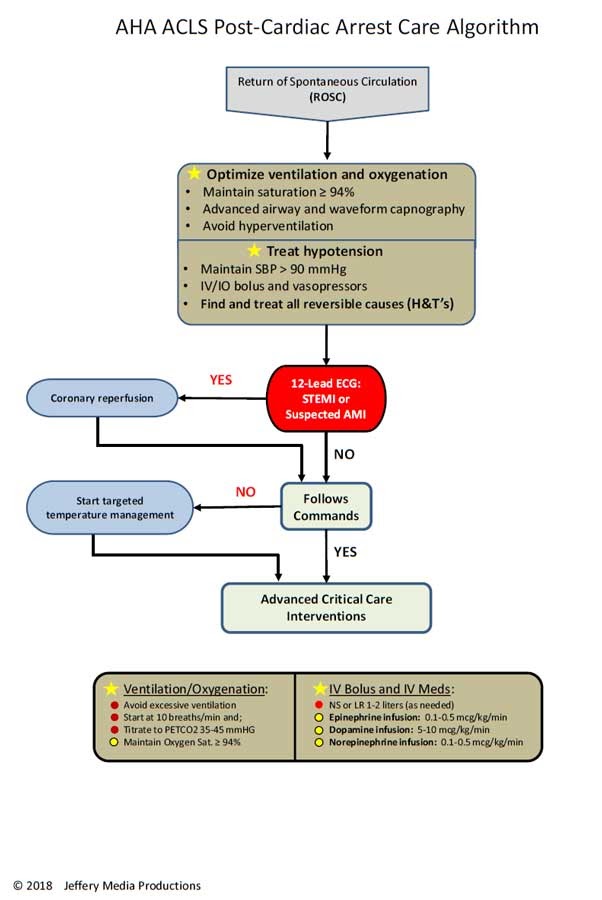

Focused Assessment with Sonography for Trauma

- High sensitivity and specificity for detecting intra-abdominal free fluid in hypotensive trauma patients.

- Four views: RUQ, LUQ, cardiac, and suprapubic

- Where you’ll find free fluid:

- RUQ: 1. Subdiaphragmatic space, 2. Hepatorenal space (Morrison’s pouch), and 3. Caudal edge of the liver

- Most sensitive area for intra-abdominal free fluid is the RUQ – more specifically, the caudal edge of the liver (contiguous with right paracolic gutter)

- LUQ: 1. Subdiaphragmatic space, 2. Splenorenal space, and 3. Inferior pole of the left kidney

- Cardiac: 1. pericardial effusion

- Pelvis: 1. Between the bladder and uterus (in females), 2. Posterior to the uterus (in females), and 3. Posterolateral to the bladder

- Fluid in the pelvis will first accumulate in the rectouterine pouch of Douglas in females, and the posterior bladder margin in males. Prostate may be confused with free fluid but is generally more hyperechoic and discrete in structure.

- RUQ: 1. Subdiaphragmatic space, 2. Hepatorenal space (Morrison’s pouch), and 3. Caudal edge of the liver

Key learning point for this case: clotted blood is more hyperechoic and can start to resemble tissue or other structures. Easy to miss if not looking closely.

References:

- Lobo V, Hunter-Behrend M, Cullnan E, Higbee R, Phillips C, Williams S, Perera P, Gharahbaghian L. Caudal Edge of the Liver in the Right Upper Quadrant (RUQ) View Is the Most Sensitive Area for Free Fluid on the FAST Exam. West J Emerg Med. 2017 Feb;18(2):270-280. doi: 10.5811/westjem.2016.11.30435. Epub 2017 Jan 19. PMID: 28210364; PMCID: PMC5305137.

- Ultrasound Guidelines: Emergency, Point-of-Care and Clinical Ultrasound Guidelines in Medicine. Ann Emerg Med . 2017 May;69(5):e27-e54. Doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2016.08.457.

- “Fundamentals.” Core Ultrasound Courses, courses.coreultrasound.com/courses/fundamentals. Accessed 2 May 2024.