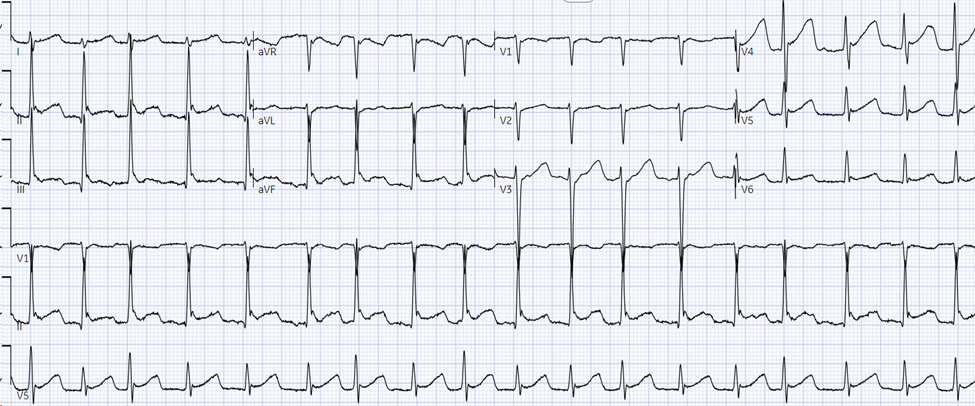

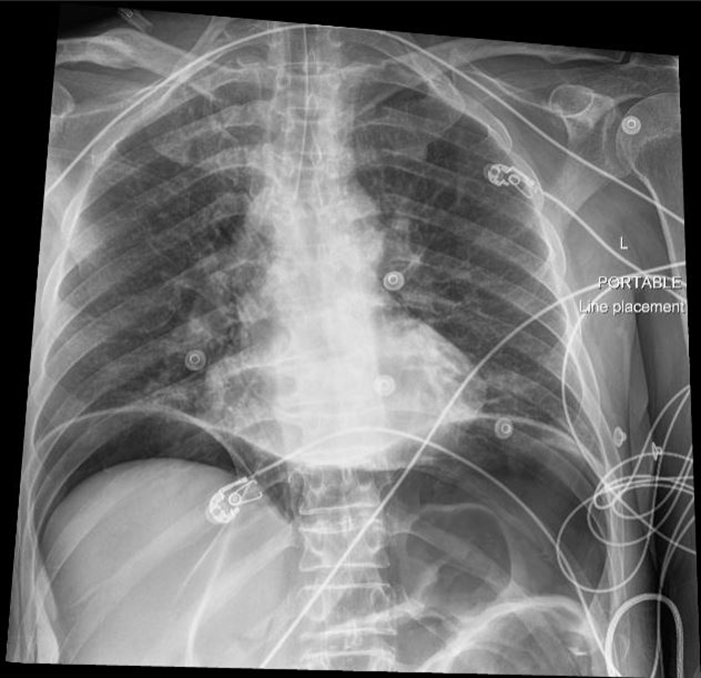

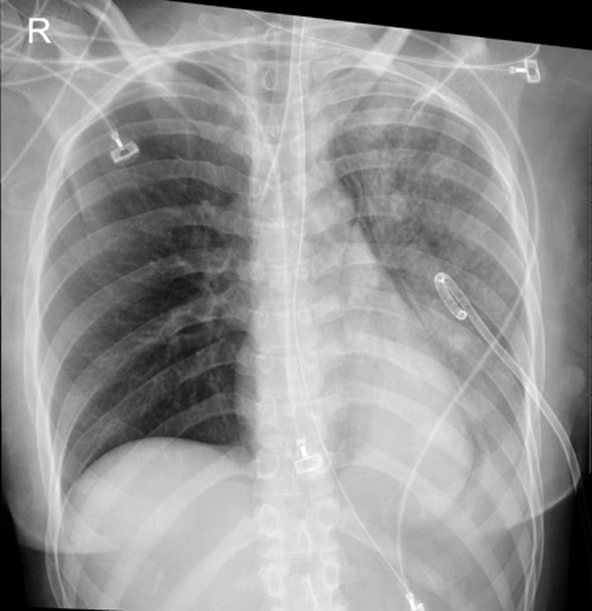

A 40 year old female presents to the emergency department via EMS for shortness of breath. Prior to arrival to the ED, the patient was hypoxic and in severe respiratory distress with absent left lung sounds prompting needle thoracostomy and rapid sequence intubation by EMS. Vital signs are BP 108/70, HR 102, Temp 98F, RR 16, SpO2 99% on 50% FiO2. A left sided chest tube is placed without complication. Chest x-ray confirms appropriate positioning of the endotracheal tube and chest tube with expansion of the left lung. Four hours later, the ventilator is alarming due to elevated peak and plateau pressures. SpO2 is 90%. There is no change with suctioning. A new chest x-ray is obtained and is shown below. What’s the diagnosis?

Answer: Reexpansion pulmonary edema

- Reexpansion pulmonary edema is a rare but potentially fatal complication following drainage of a pneumothorax or pleural effusion. The pathophysiology is poorly understood but is thought to involve an inflammatory response leading to increased pulmonary capillary permeability.

- Risk factors include large size pneumothorax, large volume pleural effusion, rapid reexpansion, and prolonged duration of symptoms (> 72 hours).

- Prevention includes limiting drainage of pleural effusions to a maximum volume of 1.5 liters in one attempt.

- Imaging will demonstrate unilateral airspace opacities in portions of the lung that were previously collapsed.

- Treatment is supportive with supplemental oxygen and observation. Most patients recover without adverse outcomes.

References:

Nicks BA, Manthey DE. Pneumothorax. In: Tintinalli JE, Ma O, Yealy DM, Meckler GD, Stapczynski J, Cline DM, Thomas SH. eds. Tintinalli’s Emergency Medicine: A Comprehensive Study Guide, 9e. McGraw-Hill Education; 2020.

Asciak R, Bedawi EO, Bhatnagar R, et al British Thoracic Society Clinical Statement on pleural procedures Thorax 2023;78:s43-s68.

Morioka H, Takada K, Matsumoto S, Kojima E, Iwata S, Okachi S. Re-expansion pulmonary edema: evaluation of risk factors in 173 episodes of spontaneous pneumothorax. Respir Investig. 2013;51(1):35-39. doi:10.1016/j.resinv.2012.09.003

https://radiopaedia.org/articles/re-expansion-pulmonary-oedema