12-month-old who was born full term is brought in by mom after patient was found to be cyanotic. Patient with vaccines UTD. Patient has been teething and mom notes that she has been applying benzocaine teething gel. Patient on arrival to the ER has perioral and digital cyanosis. His vital signs are as follows: T- 98.6 rectal; HR- 140; RR- 35; BP- 94/56; SpO2- 89% on RA. Patient is given blow by O2 with no improvement to oxygenation. What is the diagnosis?

- Patent Foramen Ovale

- Aspirin Toxicity

- Methemoglobinemia

- Iron toxicity

- Carbon monoxide poisoning

Answer: C. Methemoglobinemia

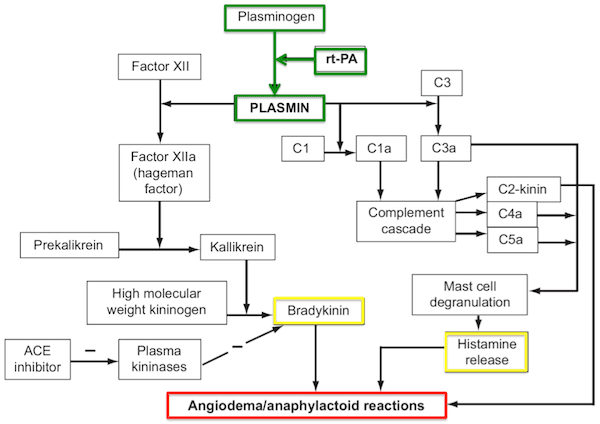

Patient has methemoglobinemia from the application of benzocaine for teething. Methemoglobinemia occurs when iron is oxidized from the ferrous (Fe2+) to the ferric (Fe3+) state. The ferric hemes of the methemoglobin do not bind O2. The ferric heme in the hemoglobin also has an increased affinity to O2 and therefore causes the hemoglobin dissociation curve to shift to the left causing less oxygen delivery.

Farkas, Josh. “Methemoglobinemia.” EMCrit Project, 2 Oct. 2021, emcrit.org/ibcc/methemoglobinemia/.

Madrazo, Lorenzo. “Methemoglobinemia.” The Intern at Work, 31 Oct. 2021, www.theinternatwork.com/infographics-2/2021/10/31/methemoglobinemia.

Swaminathan, Anand. “CORE EM: Methemoglobinemia.” EmDOCs.net – Emergency Medicine Education, 28 Dec. 2018, www.emdocs.net/core-em-methemoglobinemia/. Accessed 31 May 2024.