Otitis Media with Effusion by Dr. Sean Coulson

References:

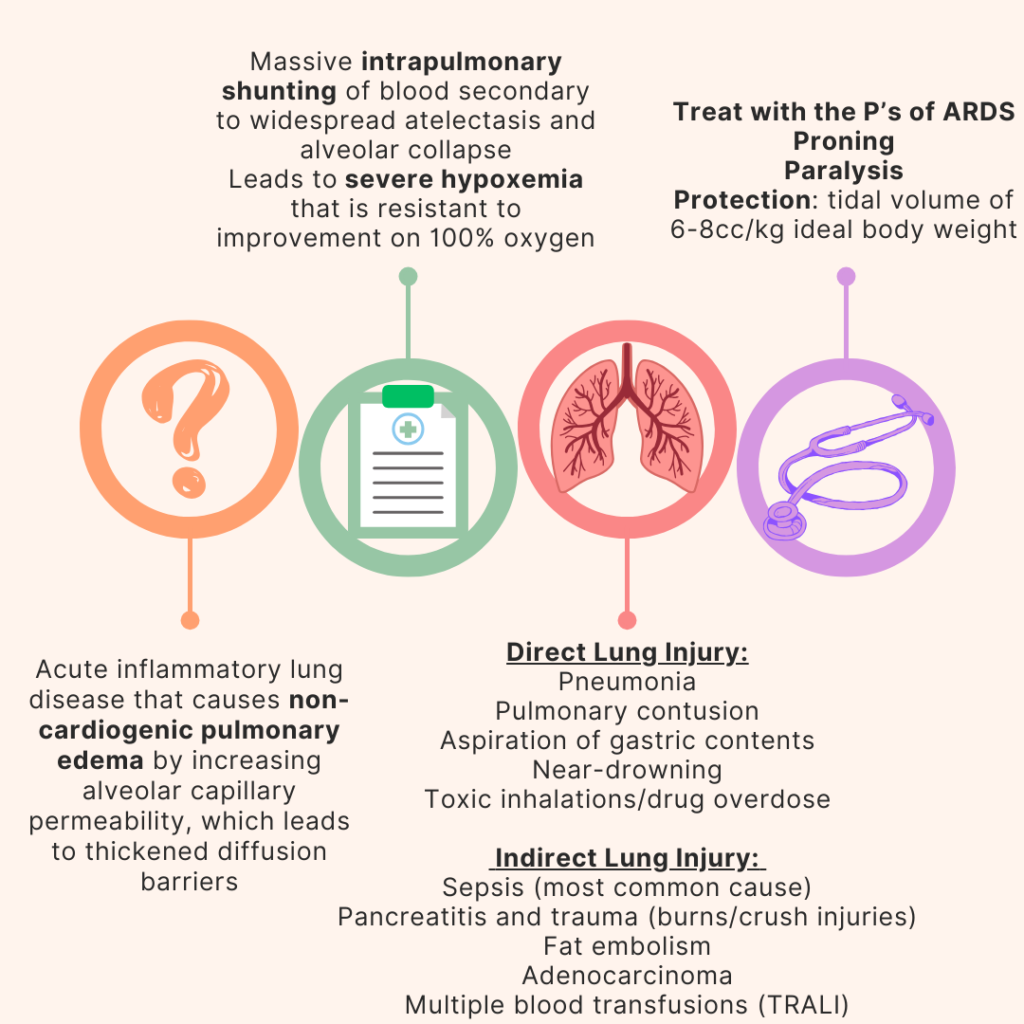

Nickson, C. “Improving Oxygenation in Ards.” Life in the Fast Lane • LITFL, 3 Nov. 2020, litfl.com/improving-oxygenation-in-ards/.

Hess, D. R. “Recruitment Maneuvers and PEEP Titration.” Respiratory Care, vol. 60, no. 11, 21 Oct. 2015, pp. 1688–1704, https://doi.org/10.4187/respcare.04409.

Emergency Medicine physicians are expert diagnosticians, resuscitationists, and proceduralists. The process of obtaining informed consent from patients in our care is also an important part of our practice. The exception is acutely life-threatening situations when timely action is required to prevent death or serious harm, whereby consent is implied.

There are 3 components of informed consent in medicine:

Some pearls regarding informed consent:

These conversations are not easy in the chaotic ED, where time is extremely limited, and our patients are usually meeting us for the first time. This underscores the importance of gaining trust early in the physician-patient relationship – a skill cultivated by communicative and compassionate Emergency Medicine physicians.

References:

1. Magauran, B. (2009). Risk management for the emergency physician: competency and decision-making capacity, informed consent, and refusal of care against medical advice. Emergency Medicine Clinics of North America., 27(4), 605–14, viii. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emc.2009.08.001

2. Moore, G. P., Moffett, P. M., Fider, C., & Moore, M. J. (2014). What emergency physicians should know about informed consent: legal scenarios, cases, and caveats. Academic emergency medicine: official journal of the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine, 21(8), 922–927.

Key Questions

How long ago was is placed? Is it a tracheostomy vs a laryngectomy?

Infections

Mediastinitis, tracheitis, pneumonia, lung abscess/aspiration, sternal septic arthritis, cellulitis, fungal infections

Consider a tracheal aspirate culture, suction, hypertonic saline, humidified oxygen

Mechanical Complications

Decannulation or Dislodgement

Tracheostomies < 7 days old require replacement with direct visualization (fiber optic visualization)

Tracheostomies > 7 days old may be re-inserted blindly (but should confirm with fiber optic visualization)

Tracheal Stenosis

Can occur at any point along trachea -> look for stridor

Location of stenotic lesions may make mechanical ventilation or criccothyrotomy difficult, or may require a much smaller airway (consider pediatric sizing). This is a surgical emergency! Consider Heliox to improve laminar flow for oxygenation.

Bleeding

Tracheoinnominate artery fistula & hemorrhage

Majority within 4 weeks of trach placement

Even if small amount of bleeding, take seriously as these are often sentinel bleeds and can lead to massive hemorrhage in 24-48 hours

Treat with external compression to sternal notch, over inflated tracheostomy cuff, consider intubation from above. Consult your surgical/ENT colleagues for evaluation and assistance

References:

https://www.emrap.org/corependium/chapter/reckOdDn9Ljn7sBLy/Complications-of-Tracheostomies

https://rc.rcjournal.com/content/50/4/542.short

https://www.enteducationswansea.org/trachy-lary-differenceshttps://basicmedicalkey.com/larynx-and-respiratory-system/

Definition: Hypertension (diastolic >120) + end organ dysfunction

History Pearls

| Neurological | Visual changes, vomiting, seizures, focal motor or sensory deficits, confusion |

| Cardiac | Chest pain, abdominal or back pain, palpitations, syncope, dyspnea |

| Renal | Anuria, hematuria, peripheral edema |

Exam Pearls

| Neurological | Focal neurological deficits, papilledema, retinal exudates or hemorrhages, AMS |

| Cardiac | Unequal pulses or BP, pulsatile abdominal mass, new murmurs, carotid bruits, rales |

| Renal | Peripheral edema |

Manifestations of Damage

| Neurological | Retinopathy, encephalopathy, SAH, intracranial hemorrhage, acute ischemic stroke |

| Cardiac | Aortic dissection, AMI or ACS, acute heart failure, pulmonary edema |

| Renal | Acute renal failure |

Special Considerations

References:

Why use facial blocks?

How do you perform facial blocks?

| Block | Anatomy | Guidance |

| Supraorbital | Branch of frontal nerve which continues superiorly Branch of frontal nerve which continues medially | -Supraorbital foramen is 2 cm laterally from nasal aspect of orbital rim-Block both the supraorbital and supratrochlear nerve by directing the needle first cephalad and then medially toward nasal spine |

| Supratrochlear | ||

| Infraorbital | Branch of maxillary nerve which continues medially and caudally | -Infraorbital foramen is below the orbital rim at intersection of pupil and nasal alae -Intraoral approach: inject into the buccal mucosa at canine and direct upward and outward -Extraoral approach: laterally approach foramen until bone is hit, inject local anesthetic |

| Mental | Branch of mandibular (alveolar) nerve which continues medially | -Mental foramen in line with premolar tooth -Intraoral approach: retract lower lip and insert needle into mucosa of first premolar tooth, inject down and outward –Extraoral approach: approach foramen laterally |

References

Gibbs MA, Wu T. Local and Regional Anesthesia. In: Tintinalli JE, Ma O, Yealy DM, Meckler GD, Stapczynski J, Cline DM, Thomas SH. eds. Tintinalli’s Emergency Medicine: A Comprehensive Study Guide, 9e. McGraw Hill; 2020.

Davies T, Karanovic S, Shergill B. Essential regional nerve blocks for the dermatologist: part 1. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2014 Oct;39(7):777-84. doi: 10.1111/ced.12427. PMID: 25214404. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1111/ced.12427

Sola, C., Dadure, C. D., Choquet, O., & Capdevila, X. (2022, April 26). Nerve blocks of the face. NYSORA. https://www.nysora.com/techniques/head-and-neck-blocks/nerve-blocks-face/